Surface Reading

Courtesy of The National Gallery of Art

I’m sitting on an iron bench in an uptown library courtyard that is sunnier or shadier depending on the way the breeze shakes the branches of the trees, and again I’m watching a YouTube video called “King George Court Memories.”

Freeze-frame at 35:00, small girl in black-and-white dress. She’s standing on a gray wood porch and smiling with very red lips and talking to a frizzy-and-black-and-short-haired friend named Laura Grant. Her own long brown hair falls in strands at her shoulders. The breeze plays with it. Her face is somehow angular, cheeks sloping steeply up to the bridge of her nose, not at all like the soft face I know so well. It's as if aging has had an effect analogous to the dulling of a blade, a not uncommon story about aging. Her cheeks belong to a separate reality from the filmy background. They pulse and glow, and I could almost pry them from the screen, like for a bug or a sticker. Let them wriggle in my palm.

Just for a moment I can see my mom in this girl, below the surface, with a face that has always reminded me of the most elegant triceratops. A white watch sits at her pale wrist.

I un-pause the video. I’ve watched it for weeks, ever since an uncle discovered a box of home videos in a literal attic and collated years and years of them into something with lots of weird non-sequitur cuts that he then uploaded to YouTube. I’m responsible for around a third of the video’s fifty-seven views, but when it plays, it becomes as strange to me as the first time I saw it. I can no longer find my mother: in movement, she becomes strange. The brown-haired girl says something to a giggling Laura; her hands rise from her waist and then together in a soft little clap; she bends forward, sways, then opens her mouth as if to bite down on some youthful squeal of pleasure and looks straight into the camera.

By now, I’ve got some distance from the disappointment I still feel when she looks into the camera but does not see me. While watching, I almost believe she’s really there. She seems so immediate, so cheerfully vibrant, so free. Free, by which I mean to say that nothing was inevitable, not her job, not my father, not me: she could’ve lived differently and loved others. Here it occurs to me that the girl wouldn’t recognize me. She’s never met me, and if she did, even if she were to get to know me, she still might not like me. I’m not so good with people, with girls. Faced with how different she looked back then, I wonder: did it change her so thoroughly, shake out the laundered sheet of her, her becoming-woman, giving birth to and loving me?

***

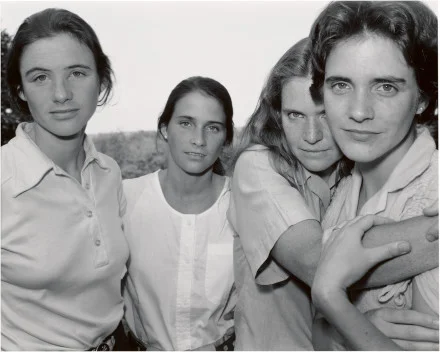

I get up, go inside. The image of that young girl floats beside an image of my mom as the woman I know now. I two-at-a-time the stairs to my Eastward-facing alcove on the third floor with my backpack and my books. Among them, a fat yellow forty-year-anniversary-edition art book of Nicholas Nixon’s portrait series, The Brown Sisters. It’s a collection of annual photos of Nixon’s wife Bebe and her three sisters, starting in their teens and early twenties and standing in the same order every time: Heather, Mimi, Bebe, Laurie. Although this can’t be how Nixon ever intended it, the series has come to function for me as a step-by-step, year-by-year document of the aging process, my data on becoming-woman.

The series is strangely moving but also, like my own family, embarrassingly suburban and banal. The first photo is a vision of youth like my King George Court memory. In 1975, the Brown sisters from their heads to their knees, against lawn and woods, a New England blasted heath. They all wear white shirts, but with variations (collared/collarless, tucked/untucked, buttoned/unbuttoned), which I am tempted to read as symbols of personality. Bebe’s pants are white too. Hands in her pockets, she stares hard, head cocked to the side. Try me. I feel chastened. I’m seventy-five percent sure Laurie has a Band-Aid on one finger. Mimi has her right arm around Heather, whose own arm crosses her waist at a painful-seeming angle.

The sisters look like girls. Young. But how to quantify this, to notate it? Roundness in the face, something unformed and quivering in the gaze? Two competing explanatory models: Do these women accrete into themselves, gathering more of themselves to themselves as they grow? Or the opposite: to come into the world block-like and undifferentiated, and what life is is being chiseled, becoming sculptural. And as to my mother, the same question: how did she grow?

***

I get chilly and head back outside. Only occasionally, as I sit writing and watching, do I remember the being whirling around indeterminately somewhere four states away and walking to work in heels and drinking less coffee now per doctor’s orders to help with her anxiety. It all too easily becomes an abstraction.

So I try to get personal. My mother making dinner nightly, checking the Weather app constantly. Her sisters had left the beach house with their boyfriends for the se, while she mostly kept to her room for two whole weeks, vowing herself to a nunnery in a notebook. As a Kindergartener, I listened outside the cracked white door to Their Room, while Mom and Dad yelled, then Mom burst out into the hall crying, and I yelled, “What did you do to her,” and she said, “It’s OK, honey.” It was hard to explain. She had the most terrible menopause, stomachaches that cut all the way through her, hot flashes, restless legs. I kicked my own little legs in solidarity. My sense of my parents’ relationship grew like a tree, so that from day to day I saw no change and only rarely looked down from the branches at the distance to the ground: something begun before me and finishing without me. I felt light and young. Somehow sunlight dappled between overlapping leaves.

She texts me, “Please call now.” With the punctuation. All her whirling around indeterminately four states away has somehow made contact with me anyway. She was working today in her small spring garden in D.C. as I wrote in New York, in the library courtyard. She came inside, washed her hands, went upstairs, and opened a large pink gum container on my shelf. Inside, a plastic bag filled with large, blue Vyvanse 20 mg. capsules. With them I can focus and I don’t need to sleep. Also inside, teensy white oxycodone 10 mg. pills, with which I can ease the awful tight-chested comedowns. It occurs to me, charitably, to point out that none of these drugs would have been discovered if they’d been consumed. Mom laughs harshly. The issue of trust has been raised, and things do not look good. I’m twenty years old, I’m considering a buzz cut, and things do not look good.

***

After my mom calls, my writing comes less quickly. I think of Henri Lefebvre’s The Missing Piece, a book about quasi-legendary historical objects lost to time: e.g. the Stephen Hero draft Joyce threw into the fire, Milena’s missing letters to Kafka, etc. But Lefebvre responds to this loss with the pure minimum, just the names, no commentary, listed fastidiously for over eighty pages. Was he worried about saying too much, saying the wrong thing? His question and mine too: how not to sound so goddamn melodramatic. Losing an item isn’t like losing a person, even if that item is another kind of you (young book: a draft; or young body: a little girl). My mom’s right as rain, whirling around four states away and calling me all full of displeasure. But there’s also a little girl who’s gone for good, relegated to a few pictures in the basements of relatives (one of my mom and her six brothers and sisters lined up in profile oldest-to-youngest at a little-league dugout), relegated to the dim memories of a wrinkled coterie at the far end of the table at Christmas Eve dinner, relegated to a YouTube video with eighty-two views; and aside from these Pieces, vanished. Tasteless, odorless, untouchable.

Somehow though, this abstract senselessness of time can once in a while harden into something more. What I see in the video isn’t so much my mom as time itself. And, dear reader, I can report that on the body of the girl who became my mother time seems infinitely moving. For a moment, I have an organ for time like the tongue for taste. For a moment, my eyes are enough.

My mom’s been at times, especially when I was my most teary and wilted, one of the closest people in my life, testifying to the possibility of my angsty inside coming into the 3-D outside (what the fantasy of home is all about). I’m a high schooler sobbing after my first real heartbreak, and it’s a hellish and lamplit 4 a.m., and she’s holding the tissues. I’m mute and recumbent in the ER, and doctors are seeing what they can do about my ears, which are seriously impacted on account of my blood flowing dangerously fast, my heart beating actually painfully fast, all on account of me doing 100-meter dead-sprints on a far too-large dose of prescription amphetamines, and she’s breathing calmly, keeping it together somewhere near my feet.

I can see shored-up patterns in Mom’s aspect, the lips pursed against impoliteness that made me as a child hang my head. But in the video she’s light and free, and what’s maybe most moving about it is that, while she seems so achingly new and unspoiled, she’s on the other hand X-marked by my awareness of the precise, inevitable-seeming path to the woman she becomes. And I suspect this double feeling for innocence and the end of innocence was what she felt watching me when I was young, teary, and wilted.

But just as I’ve begun to understand, tentatively, what my mom’s relationship to me might be like, just then the fact of her love and care for me compounded over years cuts jaggedly back and forth all the way around our relationship, a soft well-wrapped package. It rips open.

I’m trying to understand how this little girl became my mom, and I’m making up for the ripped-open quality of my imagination about her through sheer crudity. Crudity as in strictly physically: if I can’t know her any other way, I’ll learn the scientific facts. How her skin aged, how she gained and lost weight, after she blew her nose, what happened next. Anything about us we dismiss as other than the essential core of us: that’s my research project.

A working theory: you’re knowable and known. More of you is on the outside than you could ever want. I see you—you, the front of the head, the raw skin on a fresh face.

This is why I’ve been looking at Nicholas Nixon’s The Brown Sisters photo-series, which I don’t really like or find particularly incisive, but which exhibits a type of gawky heavy-handedness in the face of time and change that wins my sympathies every time. My catalog on aging, kitschy as it is. And after hours of looking, I know that the girls are inside in ’77, ’89, ’94 (maybe), ’97, ’13 (maybe), ’14 (maybe). That Mimi is the only one of them to show her teeth, something she does in ’80, ’88, ’89. She’s pregnant in ’92. They all smile in ’88. They look so beautiful in ’81.

But what I hoped would give me a thesis (the outdoors, tight lips, infertility, frowns, banality) that I could apply to my mother, turned out to add up to nothing, nothing more than a predominance, merely the raw probability of what will happen in these photos. One of the problems with looking is that you get so good at seeing what you’ve already seen.

***

Nixon’s series takes me back to the history of the Family Photo. My mom insisted we take about a dozen. It was like my face just couldn’t smile, and the longer we posed the frownier I’d get. Family photos are democratic in access (access to some sort of camera, some sort of family). And aside from a bit of formal tidiness, Nixon’s photos feel so democratic that we could’ve made them ourselves, which means they often seem not just understated or accessible but boring the way your own photos are boring.

Strategies I’ve developed against this boredom: for example, I decide that in the ’76 photo Laurie looks strange, changed. It’s easy to forget how long a year is when all I have to do is lick a finger, turn a page. Now though, she’s stony-faced as ever against a long field, bosque at the horizon, another blasted heath, she seems a decade older in her eyes, steely and clever with her new short hair. The wiry equine girl from ’75 gets condensed like a slinky, boyish and lean like a stray. A silly question: did Laurie at ten become more herself, more Laurie when she hit fifty? I think the faddish pop-psych neologism for this is self-actualization, which is not about aging but about growing (which sounds much nicer, growing does). I tend to sign off on the idea that a year is long, that I’m always not just aging but growing, i.e. getting stronger and smarter—self-actualizing. But it could just be a lie. I think I can see the change that time has made upon these women just from looking. But is it a deep one, a growth and not just an age? And I remember myself in Kindergarten on the playground on one of the last clanging cold spring days, me sitting with a skinned knee and asking kids to leave me alone and refusing to go to the nurse and feeling scared and frustrated in a fuzzy young way, and me now with a larger number for an age but still unescapably like that after all these years, stuck in that dear untrusting little boy.

***

In ’78 everyone has freckles, is composed prettily, models for some Vineyard Vine ad. Heather: haughty; Mimi: serious; Bebe: severe; Laurie: reproachful. I think WASP. I think foxy Puritan. There’s unity of posture, the girls bunched together. Irritating. This sort of mawkish unity.

I feel excluded, frustrated, cruel. I’m not one of the sisters, not one of their brood. And not any closer to my mother through them. Not sure what I want with the photos (the unceasing disappointment of the portrait: it won’t open its mouth and speak to you), so I resort to an old tactic, stare hard at Laurie. It’s hard to know when looking becomes ogling: I’ve been speaking the language: soft cheeks, thick lashes. I attempt a pornographic relationship, a not uncommon one between a man and a picture. I summon up a vision, moving my hand slowly, pressing down into Laurie’s tiny breasts, thumbing a raw red nipple. But the image deflates quickly, half-hearted. Nothing to say here. I thumb the book stupidly: on one of the last pages, year 2012, those craggier people (more wrinkles, less estrogen), the sisters after time’s been done to them. I snap the book shut.

***

A brainless nervous habit that I’ve taken to when I tire of the Brown sisters: At 35:08 in that video, my mother as a young girl. At 1:14:02 (after numerous cuts and jumps of years thanks to my uncle), my mom on Christmas Eve thirty years later, when she’d already become recognizable to me, already had me. There’s a way to position the cursor so that, using two keys, I can toggle back and forth between these two versions of my mother as fast as my two fingers can move, creating this sort of buzzing, stuttering, 30-year-transversal image that almost puts these people back together for me and that, for trance-like periods of time, I’ve stared at, glazed-over, zombie-like on a Vyvanse comedown, worrying about what my mom will do about me and my drugs.

***

While watching Mom’s videos and scanning the Brown sisters, I’ve been reading about butterflies. About the lack of satisfying literature on butterfly metamorphosis, the high level of confusion over what exactly happens in the chrysalis. Cut one open halfway through metamorphosis, and you’ll see this pinkish goo or slime. As if the caterpillar had dissolved into the goo, which goo was somehow being rearranged into a butterfly. But what’s not just surreal but nonsensical about this is that, if you cut a caterpillar open before it enters its chrysalis, you’ll already see tiny clusters of cells looking an awful lot like little palpises and near-imperceptible omnatidia and itty-bitty wings—suggesting a totally continuous element to the transformation. Like say you cut me open and there was a whole other kind of person growing up inside of me—but this person was also me. Like being pregnant with myself.

I’ve been reading stuff like this because there’s only one experience, which I had very young, that I can imagine modelling the shock and break of transposing that girl to that women, time to new time. Our teacher bought a “Monarch Caterpillar to Butterfly Habitat,” really a column of netting in bright primary colors. Inside, caterpillar eggs. Eggs the size of periods: .

The eggs hatched. The black and orangey stripes inside them gorged on milkweed, growing 300 times in two weeks. Skin tightened until it tore, head capsules popped off—and then they ate their own skin too, with their mandibles, using thorough, circular motions.

I mean the chrysalis. The caterpillars molted for the last time. A genetic switch was tripped. Hormones pumped. The emptying of the intestines, the spinning of silk pads, the stabbing in of ventral stems. A hanging j-shaped alien forest on the netted column in the corner of our class room. From my desk I picked my scabby knees during recitations of numbers or months and saw the yellow-green shells, which deformed and hardened, turned blue-green and then opaque against the vibrant colors of wings.

Wings. The pupae broke. Butterflies emerged with wrinkled, rumpled wings, pumping fluid into them, unfolding and drying them. My favorite part was the proboscises: the straw-like tongue that uncurls to suck water or nectar.

This was the total change my big eyes on my bobbly young head widened upon, the difference in a single thing, like Laurie Brown unlike herself thirty years later, like a little girl unlike the woman who had me. –Sebastian Mazza

Sebastian Mazza '18 is from Washington D.C. and is a student at Columbia University, studying English.